How We Created the TikTokcracy Report

Article by Georgi Angelov, Disinformation Analyst at Sensika Technologies and TikTokcracy Report Lead Researcher

We began working on TikTokcracy after it became clear how the pro-Russian candidate Călin Georgescu in Romania finished first in the 2024 elections, thanks to a network of TikTok accounts publishing almost identical videos. The model was already well documented: fire hose tactics, mass replication, paid influencers, Telegram coordination, fake comments, and artificially boosted reach.

Our question was straightforward - does anything similar exist in Bulgaria? And if so, who benefits from it?

Mapping the Network: Where We Started

We opened TikTok and began with key Bulgarian political hashtags - #меч, #рудигела, #ивелинмихайлов, #възраждане, #величие, #избори2024 - recording all accounts that appeared consistently under them.

Then we identified influencers who surfaced repeatedly. We looked at:

who repeats the same phrases

who posts in the same style

who attaches themselves to the same cluster of hashtags

We also checked for reposts and stitches. If the same video circulated across many accounts, that was our first signal of coordination.

At this point, the initial map started forming: party profiles, supporting accounts, micro-influencers, pages of unclear origin, and profiles that existed solely to push specific clips.

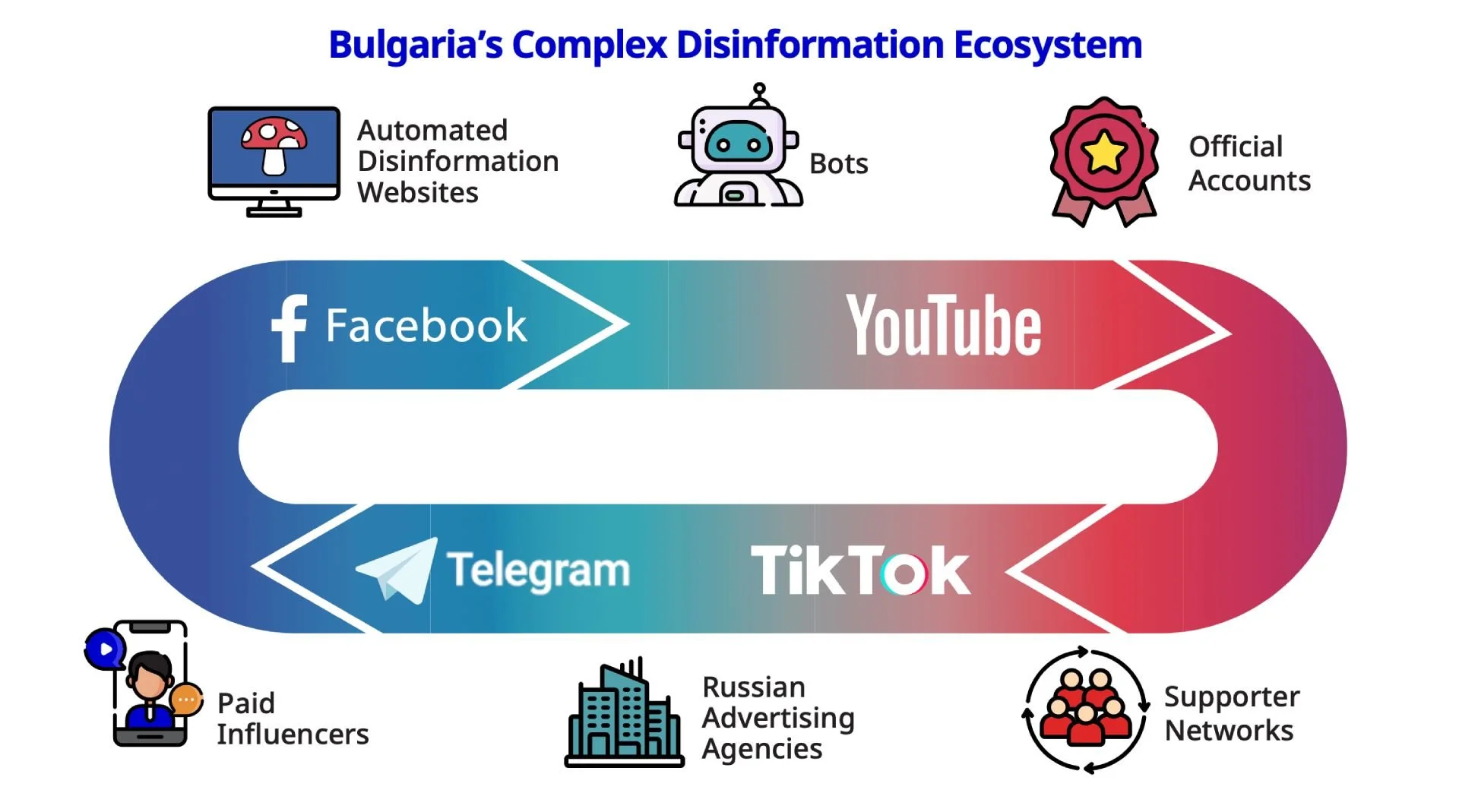

In parallel, we reviewed bios-links on Facebook, YouTube, Telegram, and websites. A full pre-election ecosystem emerged. From these observations, we concluded that Bulgaria hosts an “economically motivated system for algorithmic manipulation,” operating through a multi-platform infrastructure.

Data Collection

To measure behaviour, we downloaded all videos from the pre-election period through Sensika and pulled metadata via Exolyt. This gave us:

views

likes

comments

shares

ER (engagement rate)

timestamps

comment datasets

We used Exolyt not only as a secondary source to validate metrics but also because the platform preserves comments in the exact state they were in when its crawler passed. This mattered because many TikTok comments disappear, change, or get filtered later. In Exolyt, we could see the original discussions, as well as geographic data for some of the commenting profiles.

This is where we discovered the first geographic anomalies - comments from countries and regions that have no logical connection to Bulgarian political discourse. Similar inconsistencies are described by NATO StratCom COE (2024) and Nevado-Catalán et al. (2022) as clear indicators of purchased or inauthentic engagement.

This allowed us to move from qualitative observation to quantitative analysis.

Once we established the methodology, we shared it with our partners so they could extract equivalent data for Kosovo. This helped us determine whether the same models exist beyond Bulgaria.

The First Anomaly: Low ER with Very High Views

The first sign of manipulation is a low engagement rate paired with unusually high reach.

Normal content: ER above 3–4%

Suspicious: 1–2%

Likely manipulation: below 1%

These metrics align with TikTok benchmark data from Socialinsider, Brandwatch, and Emplicit.

In Bulgaria, we found dozens of videos with:

100–300K+ views

ER below 2%

sometimes 0.5% or 0.3%

This is not organic behaviour. It matches the model described by NATO StratCom COE (2024) and Nevado-Catalán (2022): artificially generated views without corresponding reactions.

Fire Hose Model: Repetitions, Variations, and Information Noise

We observed entire clusters of profiles posting:

the same videos

with minimal changes (different music, text, emojis)

within hours

This is the fire hose model described by RAND (Paul & Matthews, 2016), also visible in the Romanian campaign.

The goal: TikTok treats each variation as “new” content → increased reach → higher chance of appearing in voters’ For You Page.

Imbalances: Suspicious Comments and Geographic Anomalies

One of the most telling anomalies appeared in the comment sections:

monosyllabic, templated comments

repeated comments under different videos from different profiles

accounts with locations in other European countries, Asia, and the Middle East

accounts that comment actively on political content from specific parties but produce no content of their own

comments unrelated to the video

or a complete lack of comments on strongly political clips with very high view counts

This pattern aligns precisely with what Nevado-Catalán and NATO StratCom COE associate with:

purchased comments

bot comments

comments from global engagement farms

Suspicious Profiles and Cross-Platform Links

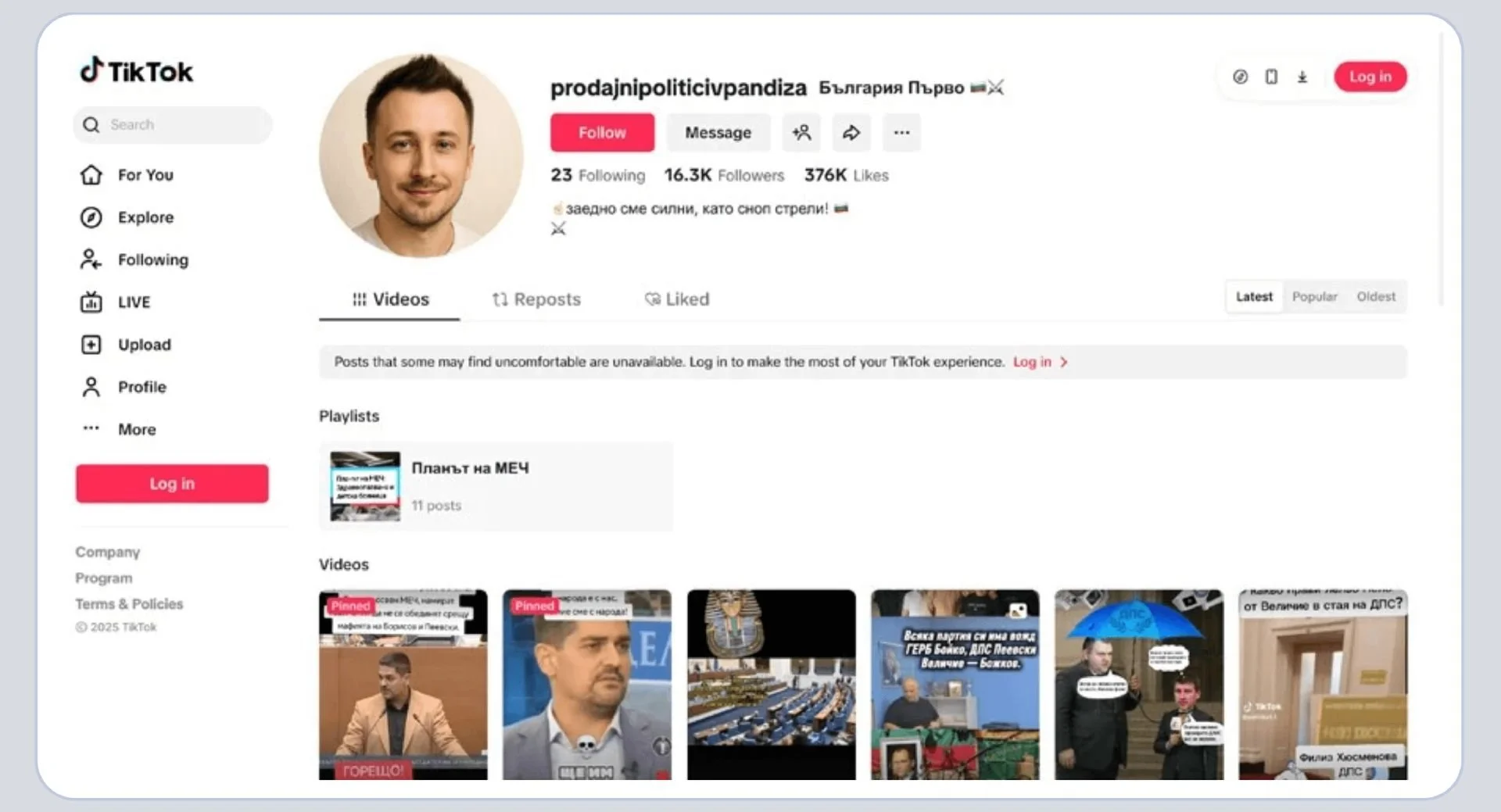

We also found profiles with clear signs of inauthenticity:

AI-generated profile photos

registration outside Bulgaria (e.g., UK, where the DSA does not apply)

content directed exclusively toward supporting one party

links to Telegram groups, Facebook pages, and websites connected to specific political actors

The BFMI & Sensika report describes a concrete example: @prodajnipoliticivpandiza - a profile with an AI-generated photo, unclear origin, and one-directional political content.

Parties and Networks: Who Runs the Largest Operations?

According to our analysis, the most active political networks on TikTok were:

МЕЧ

“Възраждане”

“Величие”

These groups displayed:

mass repetition of videos

the lowest ER with the highest view counts

the largest number of suspicious comments

the strongest cross-platform activity

the most frequent signs of paid boosts

What TikTok’s Own Data Shows

TikTok officially reported that in 2024, in Bulgaria, it removed:

423,000 fake accounts

6.4 million fake likes

328 ads violating policies

These numbers alone show that the platform was a significant target for manipulation during the election period.

What We Concluded

After combining all indicators - low ER, burst views, fire hose clusters, anomalous comments, AI profiles, cross-platform coordination, repetitive party networks, a clear picture emerged:

Organized networks in Bulgarian TikTok exploit algorithmic vulnerabilities to amplify political messages and shape the visibility of specific parties.

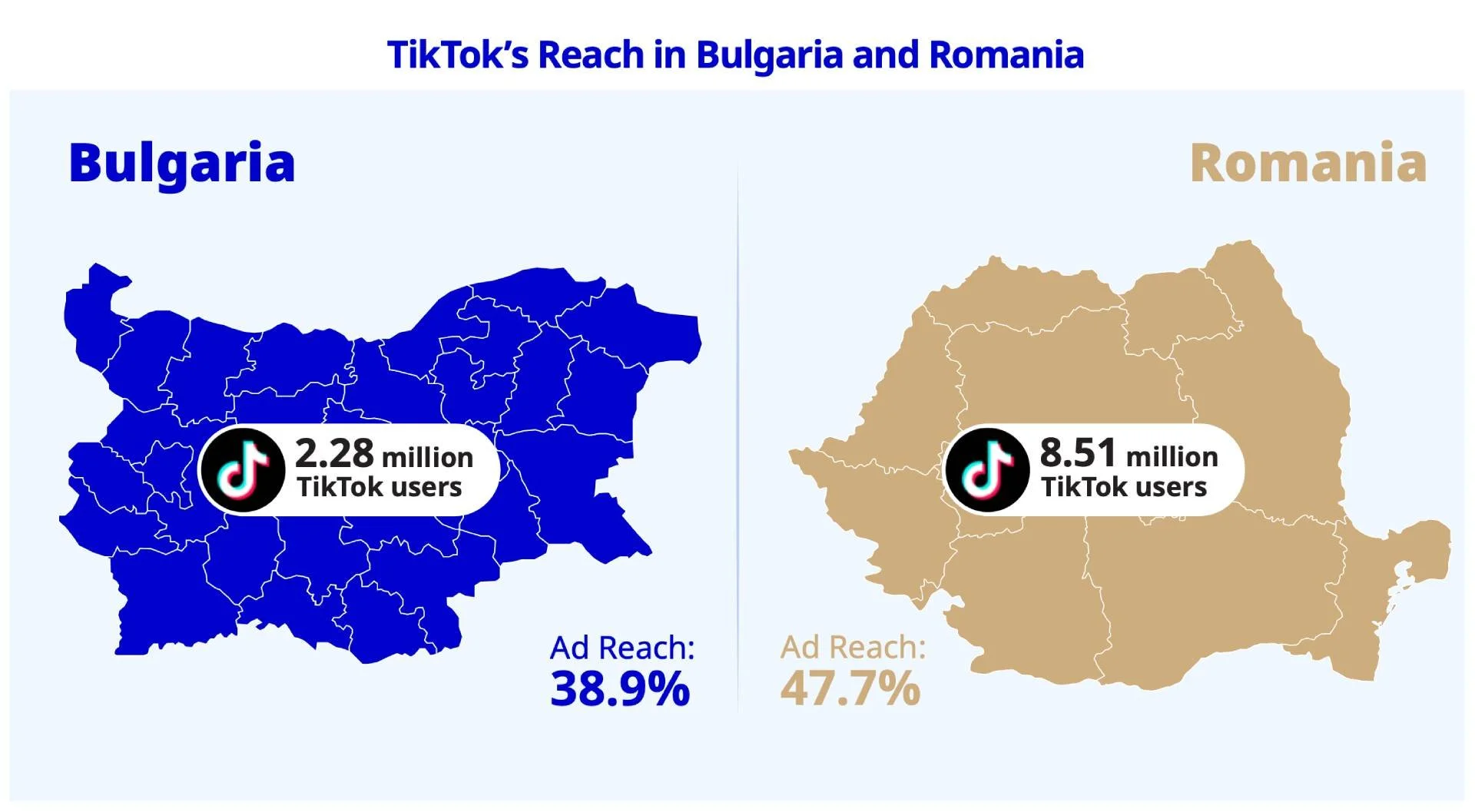

The model is almost identical to the Romanian one, though smaller in scale. It is part of a dispersed, economically motivated, continuously active system of algorithmic manipulation.

Our partners’ analysis in Kosovo showed nearly the same dynamics: TikTok enables the rapid creation of new political identities and networks that can shift public sentiment faster than institutions can respond. This new ecology of influence is described in detail in our report.

In the region, where TikTok penetration rates rank among Europe’s highest, the platform has become a kind of shadow government, with no accountability to anyone but its shareholders.

Embedded in the media and economic system, influence networks lie dormant, adaptive, and always ready to activate. In fragile contexts, like Kosovo, early-stage algorithmic interference can inflame pre-existing tensions and create instability that cascades beyond elections.

Triangulated, Romania, Bulgaria, and Kosovo show a new ecology of power in which influence is distributed across invisible networks, optimised to operate faster than human cognition, and capable of sculpting both perception and behaviour before institutions or the public can respond. Democracy is no longer a negotiation among citizens.

If virality can manufacture momentum, what does it mean to gauge public opinion? This is a question that Paris and Berlin are no doubt brainstorming ahead of approaching elections.

The southeast front is useful here beyond being a preview of the continent’s future. The illusion that electoral manipulation is a Balkan export, quarantined by borders or technical fixes, no longer holds; each electoral cycle demonstrates that in the new order, any state with a penetrable digital infrastructure is fair game.

From our research, what emerged was a hybrid system where these manipulation tactics can distort democratic processes by creating artificial consensus that shapes the perceptions and behaviours of voters exposed to manufactured trends.

Decision-making grows more reactive, less reflective, and opinion can shift according to the rhythms of coordinated campaigns designed to exploit platform algorithms. The algorithm has become an agent of democratic distortion.

Democratic self-government cannot survive on autopilot

Europe’s policymakers, facing this new terrain, are caught between inertia and alarm. Calls for a European Democracy Shield echo through parliaments and the Brussels corridors of power, but beneath the rhetoric is confusion about where to draw the line between legitimate persuasion and engineered perception.

Trust, the fragile currency of democracy, erodes quickly when voters cannot distinguish between genuine debate and manufactured consensus. The result is cynicism, withdrawal, or worse: the perennial temptation to embrace strongmen who promise order and clarity amid informational chaos.

The manipulation of engagement metrics has changed the meaning of the vote. The Southeast European experience shows that democratic self-government cannot survive the algorithmic age on autopilot.

If Europe hopes to restore genuine political agency, it must address specific challenges by, for example, strengthening platform transparency requirements, improving detection of coordinated inauthentic behaviour, ensuring clear labelling of political content, and building public literacy around manipulation tactics.

The alternative is clear enough in the TikTokcracy’s shadow: a democracy so shaped by manufactured consensus that its future will be chosen less by voters, and more by whatever coordinated campaigns happen to trend next.

Our readers read next: